Q&A Blog | World Lion Day

John Heydinger

Check out this World Lion Day Q&A blog with Dr. John Heydinger, a graduate researcher studying the desert-adapted lions of northwest Namibia and working and Lion Ranger working with local communities to prevent human-lion conflicts!

Q&A Blog

Published August 10, 2021

All images provided courtesy of John Heydinger.

Check out John’s Lion Ranger program here!

During your years of training as a historian and conservation biologist, what led you to aim your career on examining human-lion conflicts as a socio-ecological challenge and ultimately co-found the Lion Ranger program?

My interest has always been at the intersection of humans and nonhuman environments – how people interact with the world around them, focusing on sustainable outcomes that support biodiversity. My engagement with human-lion conflict (HLC) in northwest Namibia came as an outgrowth of my research on the communal conservancy system in the region. When I returned to NW Namibia in 2017 to begin my doctoral research a colleague informed me that HLC was among the pressing issues facing conservancy residents. With his mentoring I oriented my research towards the history and contemporary social-ecological challenges surrounding HLC. The Lion Rangers program was requested by the Namibian government to help limit HLC in the northwest. Along with Russell Vinjevold and Dr. Philip Stander, I was helped re-activate the group and was able to help catalyze it into the active group of local conservationists it has become.

Throughout your academic endeavours and career in environmental history and conservation biology, who did you look up to or view as a role model/mentor?

My academic mentors have been my supervisors. At Carleton College, environmental historian Prof George Vrtis and geographer Tsegaye Nega. At the University of Cape Town conservation biologist Graeme Cumming. At the University of Minnesota historian of science Susan Jones and biologist Craig Packer. At Macquarie University environmental historian Emily O’Gorman. As a conservation practitioner my mentors and heroes are Dr. Margie Jacobsohn and the late Garth Owen-Smith, who helped found Namibia’s communal conservancy system, and Lion Ranger program co-founder Russell Vinjevold.

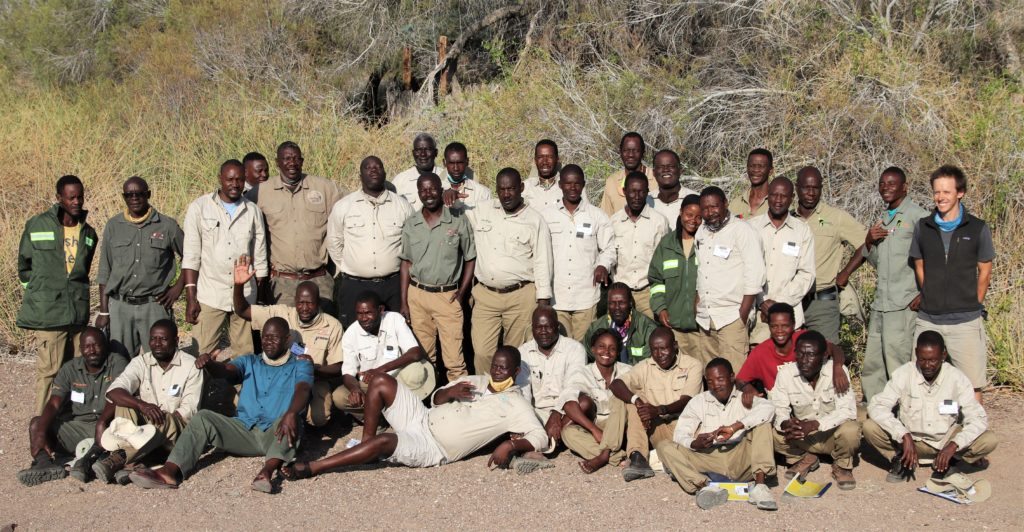

Left: Patrol Leader Jendery Tsaneb working with an immobilized lioness. Right: Lion Rangers at training, February 2021

Across your years of working around the world with big names like National Geographic and the Lion Rangers, what is a challenging encounter you’ve faced that you wish people following a similar path should know beforehand?

Among the greatest challenge facing wildlife conservationists are forging meaningful relationships of trust and equanimity with local people, many of whom bear the rights, responsibilities, and burdens of conserving wildlife. In our work there is no substitute for forging and tending to close personal relationships. By spending time with local pastoralists we learn about the challenges in their lives and about their priorities. We listen to their needs and meet them on their own understandings of how to balance human livelihoods and wildlife survival. This often means transforming our own goals and methods to mesh with local approaches. Our relationships are built on trust, even friendship. By opening our lives to the people we work alongside we develop senses of shared responsibility, not just for wildlife, but for communities, children, the landscape, and individuals. This is the community in community conservation.

Male and female desert-adapted lions near Ombonde research area.

What do you think are the most important qualities one must possess to work as a lion ranger and limit human-wildlife conflict?

Patience. Persistence. Humility. Plus, you need to be just a little bit crazy.

After studying and working with these African carnivores for years, are there any misconceptions the general public has about lions that you are eager to clear up?

I cannot speak directly to how the general public imagines lions. I have learned that lions are intensely social and often incredibly bonded to their pride mates. In our area they are generally quite afraid of people, though they are much bolder at night. Lions are incredibly adaptable and the remnant populations across Africa likely represent a small sliver of the ecosystems lions used to inhabit.

As you work to limit human-lion conflict in Namibia, have you taken away any universal values that allow humans and wildlife to coexist in harmony?

I do not know about universal values. I generally believe the more people are exposed to wildlife the greater sense of identification they will have for wild animals and the more highly we will intrinsically value them. I suppose the closest to a universal value is that bringing people together around complicated, even complex, challenges like sustainable wildlife conservation is primarily a process of building human relationships of trust. This takes time and there is no substitute for listening to people, sharing stories, arguing, debating, working together, and finding common ground where compromise, perhaps even consensus, can be reached.

Left: Desert-adapted lioness near Huab riverbed. Right: Lion Rangers patrolling Ombonde area.

The endangerment of these African carnivores may seem like a distant problem/threat to those who live in other parts of the world. To those who have not had similar first-hand experiences with these mammals like you, how can the general public get started in becoming active participants in lion conservation?

The general public appears to be reasonably well-informed about lions, and the threats facing large terrestrial mammals. I would hope that people who have the privilege to engage in conservation, rather than the necessity of living alongside these animals, would understand that humans and large predators have lived alongside one another for thousands of years, and it has almost always been a challenge. Living alongside lions is difficult, particularly when prey are scarce. There is no ‘solution’ to HLC or to wildlife conservation. Rather, the challenges shift and transform as economies, cultures, politics, and environments do. As wildlife conservationists are job is to pick up the baton from preceding generations, to do our best to carry the work forward, and hand-off to the next generation who will face different challenges. Our hope is that we leave the next generation as well situated to face their challenges as we can.